The philosophical musings of my father

- by rickrandolph

My father was not a learned man. I found an old junior college report card of his once filled with D’s and F’s and he quickly snatched it from me and stared down at it.

“I dropped out not long after this,” he said. He was embarrassed. He told me several times, even after retiring from his career as a cop, that he wanted to go back and finish his Associate’s degree.

It wasn’t that he was not intelligent, but I think it is fair to say that he did not like to think too deeply on many topics.

He was an avid reader. As he got older and grumpier, I thought it might be a way for us to connect. I read some of the cop and detective novels he loved. Admittedly, I went through a period where I was a bit of a book snob. I would only read the classics and then eventually all fiction became off-limits. But the stuff he was reading was terrible. I couldn’t do it.

Then I got introduced to John D. MacDonald’s Travis Mcgee series. Travis was a man’s man and a detective, often described as an errant knight. I took him a stack and said, “You will love these.”

A few days later, I asked if he had started them.

“I can’t read them, they started off ok but then he goes off on these monologs about the ways of the world and he loses me.”

Those are the best parts.

But this doesn’t mean he wasn’t a man of words or wisdom. He had a way of creating or adopting phrases as his own, many of which I incorporated into my vernacular, thinking they were common. I don’t believe he authored any of the phrases, his skill was in the delivery.

When things were going well, he was “shittin’ in tall cotton” — which I later learned was preferable to low cotton since no one could see what you were doing. It meant life was good.

When he was cold, he was, “Colder than a witch’s tit.” When it was warm, he’d “Sweat like a whore in church.”

When my mom got busy, he’d accuse her of trying to “Shove ten pounds of shit into a five pound bag.” As a kid, I was really confused as to why my mother would shove shit in a bag and why it needed to be weighed in the first place but I always find it a handy phrase when people bite off more than they can chew.

While I was earlier critical of his literary tastes, it didn’t mean the man didn’t have standards. He always talked about the “Crotch Novels” (Romance novels) my mother read and left lying around the house.

I remember when I was just out of high school he barged into my room one morning needing help with some work he was doing. I’d been out late drinking, and somehow he knew it, “If you want to have the party, you’ve got to pay for the band.” It became my mantra every morning in college when I had to go to class hungover. I catch myself saying it now to my son when he wants to sleep until noon.

Later, when I emerged from my room, he was in the backyard with a friend. When he saw me he shook his head, “You look like you’ve been shot at and missed and shit at and hit.” I have never heard the appearance of a hung over 20-something more eloquently or accurately described.

When I was around ten or 12, he was helping me build a fort in the backyard, he put a level on the wall to plumb it, looked at, held up a thumb and declared, “Good enough for the girls we go out with.” My father was not much of a carpenter.

I repeated it a few weeks later in front of my mother and she rolled her eyes, the same as my wife does when I say it now.

While it didn’t roll off the tongue like ‘cest la vie, he meant it the same way when he said, “Well, I’ve been kicked out of better places than this one.”

Whatever.

Que sera, sera.

A few months back I was talking to some co-workers about a guy we worked with and I explained that, “I wouldn’t walk across the street to piss on him if he was on fire.”

One of them said that was a little harsh. I spent the next few minutes explaining that I didn’t mean I thought it was a good idea to light the man on fire, however, if he was already burning, I wouldn’t exert the energy to go and urinate on him.

They could not comprehend the difference.

My father was not a bumpkin or a hick, but I think he wanted to be and so he gravitated toward the irreverent in a Mark Twain-ian sort of way. To me, he turned the turn of a phrase into an art form. He could have been an actor or a comic. He had the delivery and timing.

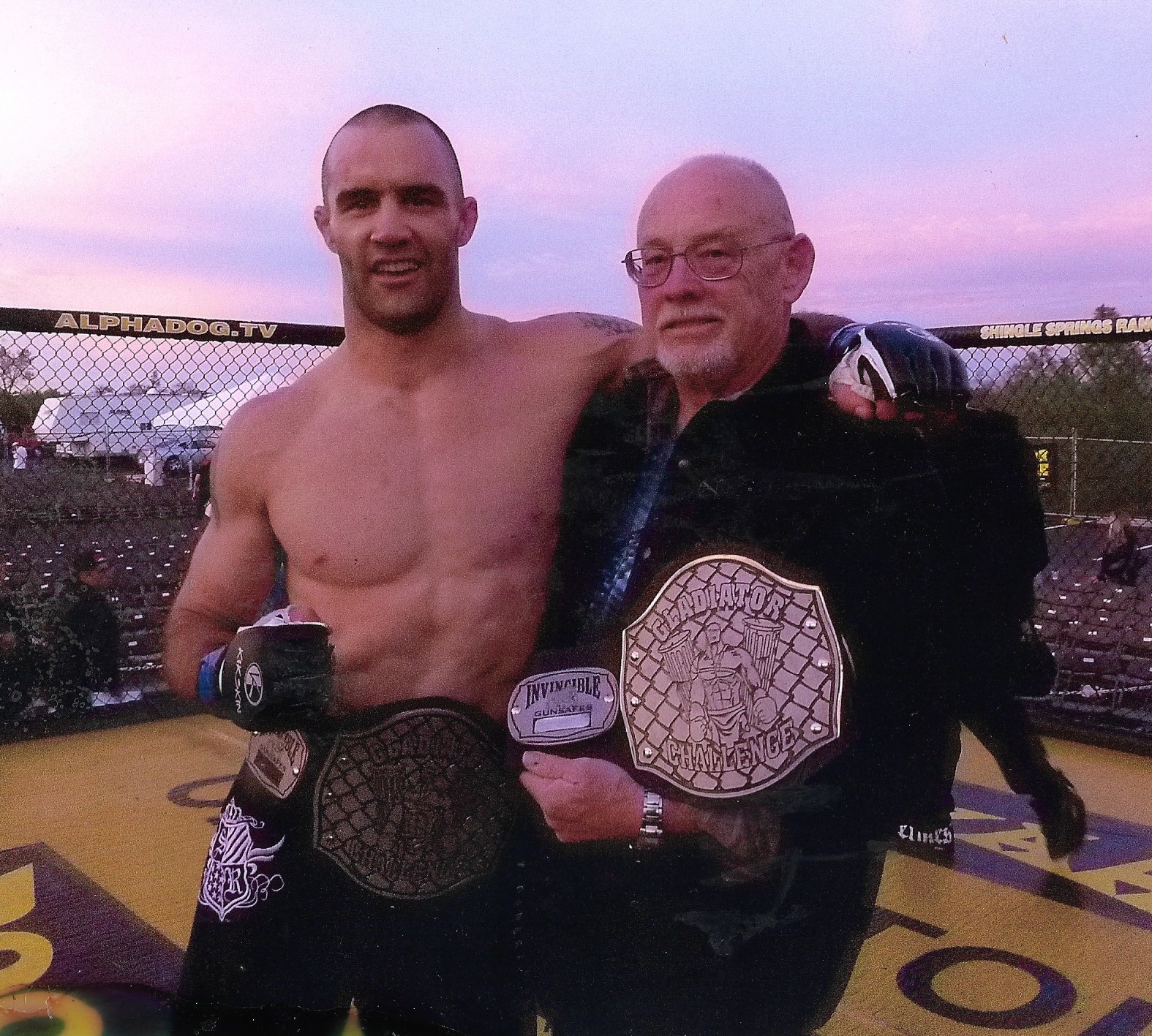

My father died in 2018. He went quickly, four days after having a stroke. I was fortunate to be able to spend most of his final days and nights by his side. He’d spent the last few years of his life pretty angry, not at anything in particular, just angry in the way men can get when they see the world changing and they don’t want it to. I feel it sometimes too. While I miss him, I know it was probably the right time, because the world wasn’t going to stop changing and the events of the last few years would have been more than he could handle. At his funeral, I opened by reminding everyone that he always liked to riff that the only reason anyone would show up at his funeral, “Was to pry open the box to make damn sure he was in it.”

A few nights ago, I was on a phone call with my mother. Life had been difficult, one of the darker times in my life, and I was bitching to her, like baby boys do. She listened and told me she loved me and reminded me of something else my father used to say all the time … and when she said it, it took me back.

When I was in my late teens, my mother moved out. She and my dad had always fought a lot and it had gotten worse over the years. My sisters had recently moved out too so it was just my dad and I. He didn’t always have a lot of people to turn to, so I sometimes got to see him at his worst. We’d go for drives and he would end up crying, asking me what he could do to get her to come back. The night I remembered we were off on some desolate road. We’d stopped driving and it was near sunset. He was done crying, and he was looking out the driver’s side window as the sun set. It must have been summer, because I remember the smell of sweat in that old scratchy truck. He took a few breaths and he said something I didn’t hear. He mumbled it again under his breath.

“I can’t hear you,” I tried.

I was always worried he would take his own life. It was why I always went with him on those drives. I figured if I knew what he was saying, what he was thinking, what was going on in those internal conversations, I could keep him safe with me. His muttering bothered me.

He turned and looked at me, breathed and said, “If we all tossed our crosses in a pile, and we saw everyone else’s, we would probably pick our own back up.”

When my mom repeated it to me on the phone, it took me back to that sunset and watching him breathe life back into himself with that very thought. I don’t remember any crying episodes after that night. Some time after, my mother and he started dating again and they moved back in together. I’d love to say it was happily ever after, but it wasn’t. They still fought but they chose each other and loved each other in their own way.

She was holding his hand when he died. They stayed together for almost 52 imperfect, yet amazing years. They made it work. They won.

I took a deep breath and told my mother that I did remember him saying that. I told her I believed it too. It was mine to bear and I chose it. Just saying that made the burden lighter.

I can still sit and chuckle at the wisdom of a man who was most proud of his billion-dollar idea to, “Install a plate glass window in some woman’s stomach so she can see where she is going when she is driving around with her head up her ass …” could also come back and remind me that real men stand up in the darkness and bear the weight.

For all of his failings, he was always there. He bore his cross. He was a religious man, a Catholic, so the symbolism was strong in his head and his heart.

And while I have chosen a different spiritual path and don’t believe as he did, I would argue it is impossible to grow up in the Catholic church and not be moved and influenced deeply by the power of the church’s imagery.

You bear the load because it is the weight of all you love. The heaviness of the burden is in proportion to the intensity of the love. It doesn’t hurt to lose the things we don’t care for. And that is why we choose our own cross out of the pile, hoist it up to our shoulders and trudge on. We are the only ones who can or will. Those that don’t love it, would leave it behind. Those that truly do, have no other choice. The weight of the others is not worth bearing.

When I look back on him it is hard to see the flaws as anything but comic fodder, nothing deeper or more significant. His struggles as a man and a father did not break or scar me, they built me. Everything he did taught me and brought me to the place I am today and I can never be anything but grateful.

So, I get to recall him, on one hand as the guy who growled and refused to waste a drop of his piss to extinguish a scorching enemy and contrast that with the man who found peace in quietly singing spiritual hymns.

My mother loved it when he would sing. It was soft and beautiful and I only wish we had recorded it somehow. It is not lost on me that when I try to recall the sound, I can only hear him singing the words to his favorite gospel song:

“And I’ll cherish the old rugged cross

Till my trophies at last I lay down

And I will cling to the old rugged cross

And exchange it some day for a crown … ”

My father was not a learned man. I found an old junior college report card of his once filled with D’s and F’s and he quickly snatched it from me and stared down at it. “I dropped out not long after this,” he said. He was embarrassed. He told me several times, even after retiring…